This year, I had the chance to teach a year-long course at EPFL about design and creative approaches with my colleague Daniel Sciboz. This class is part of the social science/art/design program which corresponds to a set of courses engineering students have to take as part of their general curriculum. Since EPFL doesn't have researchers in these domains, this program is taught by external experts coming from the University of Lausanne, the University of Art and Design Lausanne (ECAL), and the Geneva University of Art and Design (HEAD) to which I belong. Since this was the first year teaching that course, I found it relevant to describe what we did and some lessons we learned in the process.

The purpose of this course was to "give students the opportunity to discover, understand and apply various creative approaches, by highlighting the diversity of methodologies and the relevance of subjectivity or intuition". The year was divided in two parts:

- First semester with lectures and workshop activities:

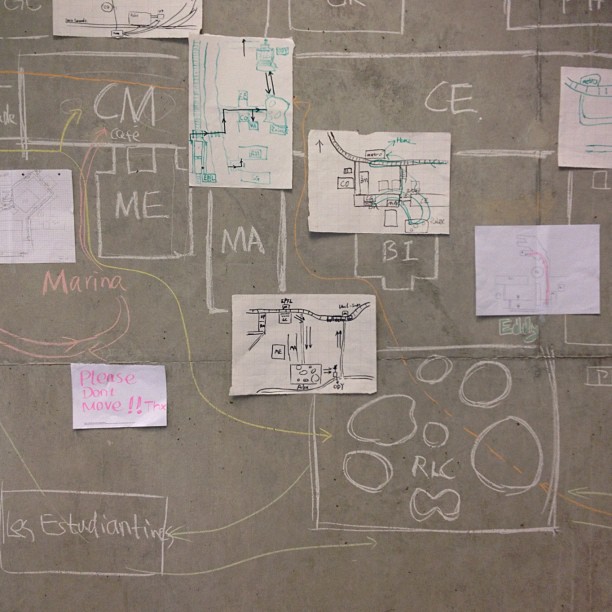

- Research and concepting approaches: ethnography (observation/interview), iconographic research, group brainstorm, mood boards.

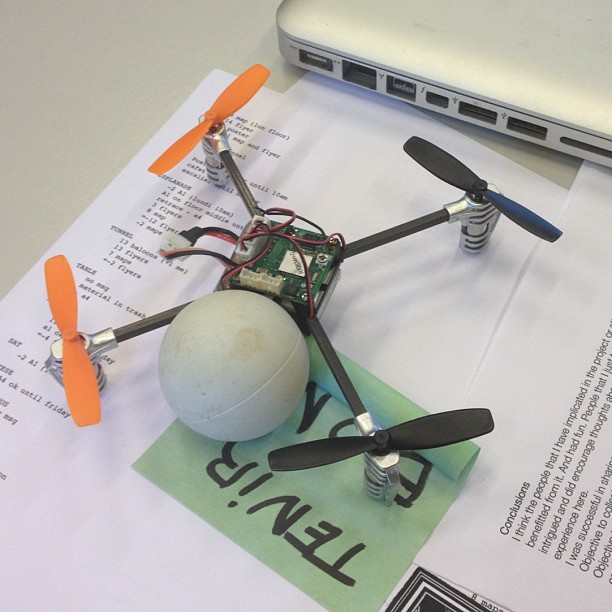

- Creation and prototyping techniques: physical and paper mock-ups, repurposing of standard software (powerpoint, excel).

- Second semester devoted to students personal/group projects.

In order to narrow down the possibilities and make the course more focused, we chose "reading in mobility" as a general topic.

Here are some remarks and comments I wrote down during the two semesters. They exemplify some of the issues we noticed and I describe them here as "difficulties" encountered by some of our students. They are quite interesting in terms of teaching design approaches to engineers and I think we may build upon these in next year's course.

One-way / One-time This is the most striking issue we noticed: when confronted with a design brief, students picked up one way to deal with it (generally the most obvious idea) and developed their answer based on that. This answer, be it a storyboard or a physical mock-up, was then implemented with lots of details without any consideration of alternative paths.

A good example of this is a student who worked on school billboards: in his "observation" phase, he noticed that they were quite messy and tedious to "update" since people had to physically go to the billboards and duct-tape his/her poster. His proposal was to design an interactive systems with displays and a web platform to update everything remotely. In this case, the student's perspective was seemingly driven by the need to complete this project quite quickly (we're competing with other classes in terms of students' attention!), his interest/expertise in computer science and his belief system (that classifies digital technology as the go-to solution for problem solving). Even when we asked him to go make other observations or "users" interviews and consider alternative solutions (with or without technologies), it was hard to make him change the course of the project.

This was certainly an "edge case" but others had similar issues as well: making observations and interviews allowed another group to redefine the brief a bit better and clarify the design space. However, once the group chose his "potential solution", they didn't want to change their trajectory, as if it was a "one-way and one-time" course without any exploration (through research and prototyping).

I analyzed this as a difficulty to deal with uncertainty: selecting the end point of their project was a good way to have a purpose and move towards it by making incremental choices. Each time we encouraged the groups who suffered from that problem, it was hard for them to cope with these advices. Either because it may alter the outcome they had in mind and because it would require too much time/energy to do it. One of them even told me that "it can't be changed at this point". My hypothesis here is that designers may be more at ease with uncertainty but I thought this was also a skill would have to master (see this paper if you're interested in the link between creativity and ambiguity/uncertainty).

A side-problem was the difficulty to use "making" as an exploration approach to problems or situations. In a very engineering-oriented way, some had to plan everything on paper (with words and sometime sketches) before building a rough prototype. Of course, we had lovely and surprising exceptions but they were less common.

The implementation bias and reluctance to iterate

Another related issue was the "implementation bias": this happened when a group of students formulated an interesting design avenue but got sucked into creating their prototype with lots of tiny technical issues. The group then had to focus on solving these problems and not thinking about the global picture. Similarly, a student was quite pissed when we told him his web prototype was highly detailed but did not correspond with the context of use he planned it for... when we asked it to redo it in a different way, he felt that what he had did before was useless and a waste of time... it was hard for him to understand that it was an important lesson he couldn't have learned otherwise.

Nevertheless, the reluctance to iterate might have been cause by the number of credits allocated to this class, with regards to others courses which are "more important" for them.

A lack of attention to formal elements and an intriguing relationship to details

We also noticed a tendency to consider formal elements and general aesthetic as something not really taken care of, or only thought of as the end of the project. It was as if some students took their project as writing with LaTeX: they focused on the "content", i.e. the substance of the project and then realized at the end they had to think about shapes, colors and how potential users may use it. This was a difficulty to consider a design project as a whole, in which the discussions about the role of the proposal and the way it's implemented (behavior, shape, aesthetic, etc.) can be inter-related.

This is quite intriguing given that some did lots of super detailed things (i.e. a list of menu items on an interface), while, at the same time, using unrealistic personas or wrong props. For instance, when a group created a video about am artifact to be deployed fifteen years ahead, the general atmosphere was not really planned to give the impression of a distant future.

Risk reluctance

When we started the projects during the second semester, what surprised me most about their ideas was the reluctance to take risks (by trying to explore weird ideas). It was as if they integrated the same risk-averse attitude as one can find in corporate culture. Especially for those who focused on direct digital transcriptions of what exist already (from visual ads to location-based ads, from messy paper-based billboards to screens). Some said things like "we have to find a real need" or "it should be based on a problem we found in the field research phase". This led to good discussions about how observations, interviews or even brainstorming can be be deployed to find ideas, which are not necessarily conventional and related to a standard problem.

We had to push them considering alternative paths and not the sole basic ideas and solution that generally already existed. Not necessarily because we only want to have weird and off projects but simply given that the point was to invent something new, beyond the current products and services on the market.

Why do I blog this? Because we're planing next year's class and it's always good to reflect on what we've done.

Maybe the main reason why these remarks are interesting for me is that the confrontation between design culture and engineering culture allows shedding some light on how designers' do things and their expectations. By looking at how designers responded differently, it enabled me to see that the assumptions I have (or the one designers have) are different from the one of engineers. It would also be interesting to write a blogpost about the common traits between both cultures, but I guess this for another occasion.

The portrait painted here might be a bit critical and negative but it was actually a great class and the comments above only express my frustration to go beyond what we've done. Most of the projects in the end had something intriguing in them. Some were more creative than others but there was always a detail that caught our attention either in the idea explored or in the implementation. This will give us ideas go modify the course next year, for instance by giving incentives to design several design iterations and alternative paths.

Also, the problems I mentioned here are not always inherent to engineers and we encounter similar issues with design students.

In

In