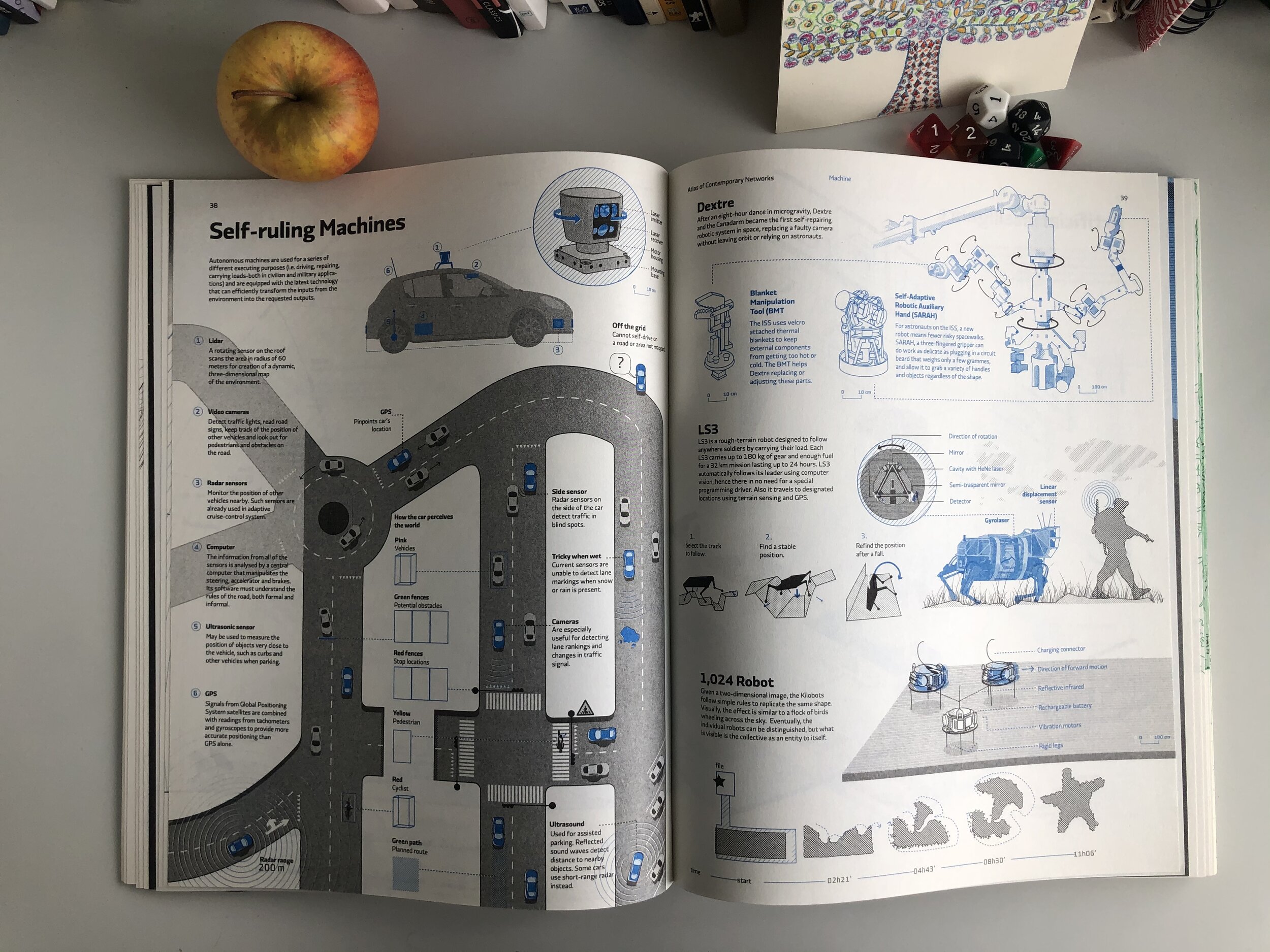

Although these technological components are fundamental, they are often invisible and unbeknown to most of us. Their existence, often dismissed as banal and purely technical, is, however both fundamental as they shape our social and political interactions.

Interestingly, there has been an increasing interest from designers, artists and social scientists towards them (see references). Based on a series of observation, interviews, and possibly research interventions (participant observation, use of non- working prototypes, probes), students will explore the potential of the digital infrastructure of the urban environment in product/service/interaction design. Can they be repurposed for other more inspiring usages? How can we combine these technical elements in order to build more habitable near-futures? Can one take advantage of existing flaws/limits? Can we protect citizens from their overwhelming presence?

Expected output(s)

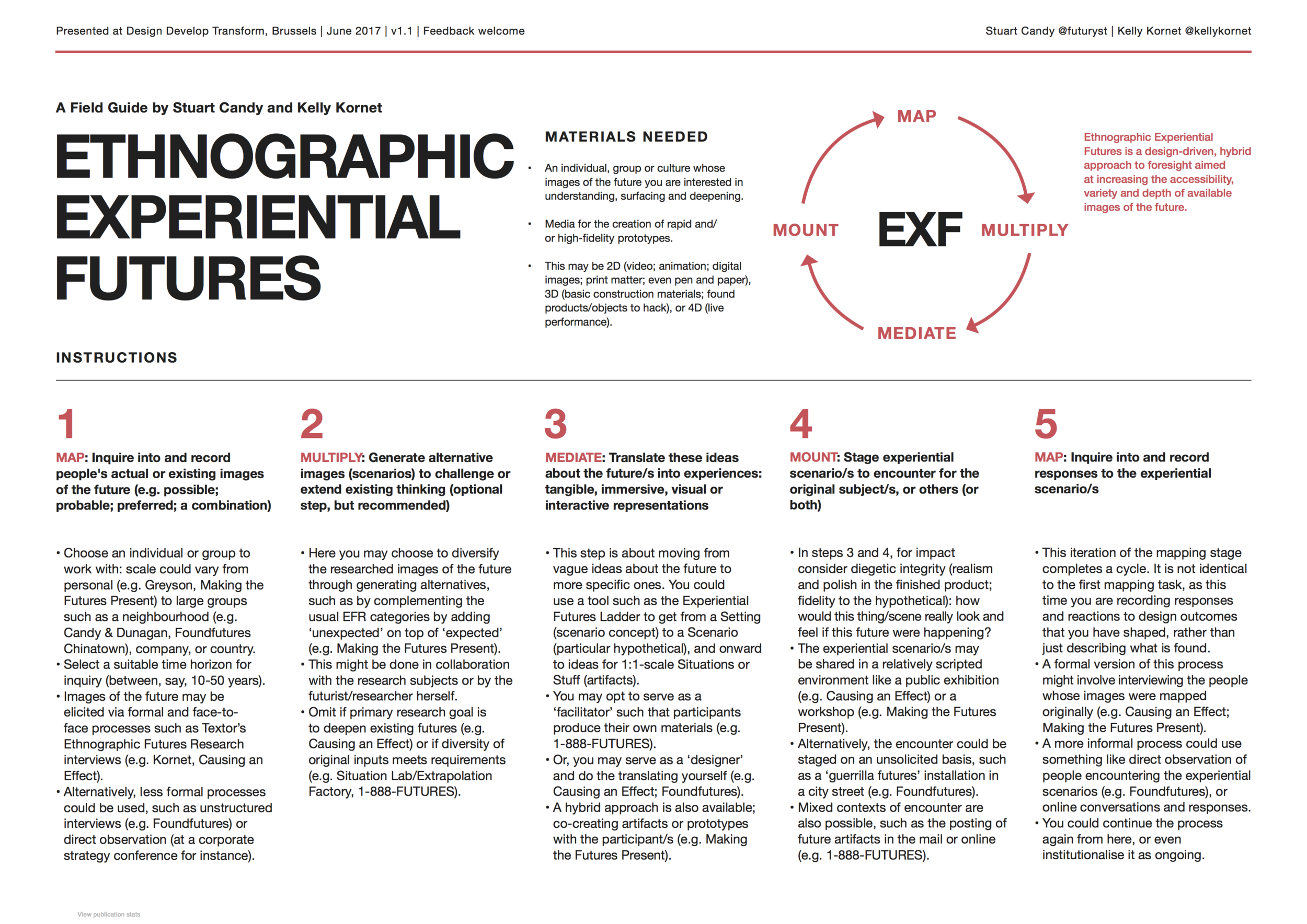

Based on both the field explorations and the process of analysing the observations, students will have to submit produce two artefacts:

Output 1: a document that summarizes the research findings (map? poster? Brief fanzine?)

Output2: an object that presents their design concept about how to take advantage of the digital infra/network. This may be done through objects, a short film, a performance, a series of drawings or visualizations; it is up to the students to select the most appropriate resolution for their outcomes.

These two artefacts will be presented orally the last day of the workshop.

Readings and references

General inspiration for field research

Perec, G. (2011). Thoughts of Sorts, Notting Hill Editions.

Perec, G. (2010). An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, Wakefield Press. Smith, K. (2008). How to be an explorer of the world : portable art life museum. NYC : Penguin Books.

Field research methods in social sciences

Causey, A. (2016). Drawn to See: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sanjek, R. (1990). Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology. Ithaca: Cornell University press.

Weiss, R.S. (1995). Learning From Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies. Simon & Schuster.

Field research methods in design/UX

Dourish, P. (2006). Implications for design, in Proceedings of the conference on Human Factors in computing systems (Montréal, Québec),pp. 541–550, ACM.

Gaver, B., Dunne, T., & Pacenti E. (1999). Cultural Probes. Interactions, 6 (1), 21-29.

Gaver, W. W., Boucher, A., Pennington, S., & Walker, B. (2004). Cultural probes and the value of uncertainty. Interactions, 11 (5), 53-56. Retrieved from http://cms.gold.ac.uk/media/30gaver-etal.probes+uncertainty.interactions04.pdf

Goodman, E., Kuniavsky, M. & Moed, A.(2012). Observing the User Experience: A Practitioner’s Guide to User Research (2nd ed.), Morgan Kaufmann.

Nova, N. (2014). Beyond Design Ethnography. Berlin : SHS Publishing. Available at the following URL.

Portigal, Steve (2013). Interviewing Users: how to uncover compelling insights. San Francisco: Rosenfeld Media.

Digital/network infrastructures in social sciences/design/art

Arnall, T. (2014). Exploring 'Immaterials': Mediating Design's Invisible Materials. International Journal of Design, 8 (2).

Augé, M. (1995). Non-places: Introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity. London: Verso.

Burrington, I. (2016). Networks of New York: An Illustrated Field Guide to Urban Internet Infrastructure. NYC: Melville House; Ill edition.

Gabrys, J. (2016). Program Earth. Environmental Sensing Technology and the Making of a Computational Planet. Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press.

Star, Susan Leigh (1999): "The Ethnography of Infrastructure", American Behavioral Scientist 43, pp. 377‐91.

Sherpard, M. (2011). Sentient Cities: Ubiquitous Computing, Architecture, and the Future of Urban Space. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Varnelis, K. (2009). The Infrastructural City: Networked Ecologies in Los Angeles. Actar.